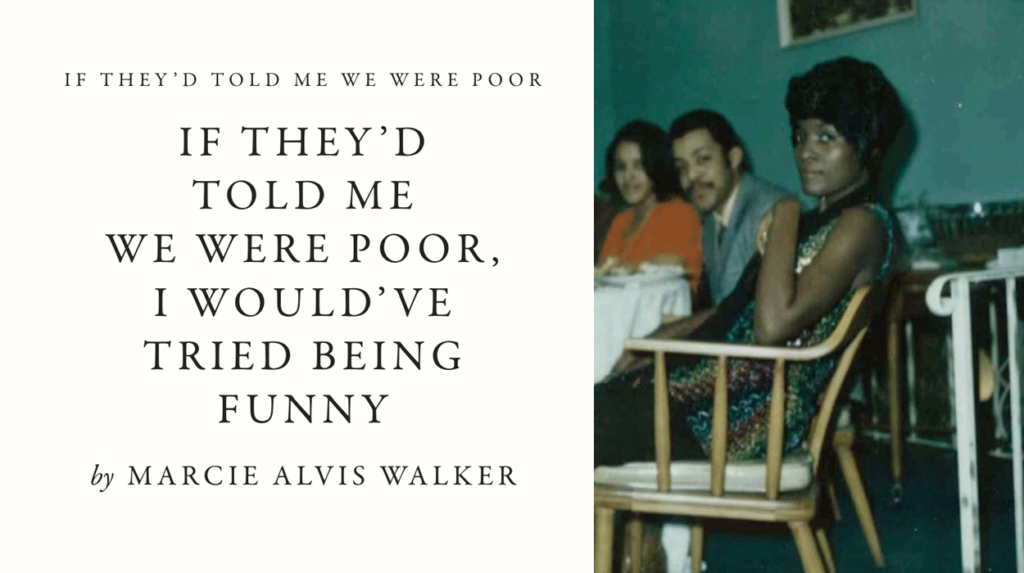

Though Marcy Alvis Walker’s family received food stamps and sometimes had their utilities cut off, her parents convinced her they were your average middle-class black family. They encouraged her to follow her dreams, telling her they could come true if she worked hard. The small problem was that Walker’s dream was an elusive one for a broke, uneducated black woman: to become a New York Times bestselling author. Now, as a published but not bestselling author, she wishes she had a backup plan.

—

In an article for Oprah magazine, critically acclaimed and award-winning author Dorothy Allison said:

What I know as a writer is that painful stories work best when tempered with humor, and when you’re describing one harrowing detail after another, it’s nearly impossible to draw the reader in unless you balance those details with the joy that life has to offer. When I work with passionate young writers, that fact sometimes seems to be the hardest for them to grasp.

“You want me to care about your character,” I tell them. “Make me laugh with her.”

And I said to her, “Dorothy, I’m not a young writer, but I’m a passionate writer. My work has never been praised for humor (it hasn’t even been, to be honest), and maybe you’re right. The problem with my memoir, which didn’t win any awards but did receive solid and generous reviews, was its heavy-handed approach to racial trauma and mental illness. If I’d sprinkled a little sweetness into it, many of my friends and family might not have felt the need to email me, after reading essay after essay of my frustration and grief, to say, ‘I’m just thinking of you, I hope you’re well,’ or ‘If you ever want to talk, I’m always here to listen.’ Maybe you’re right. Maybe I should have added a little more levity.”

Remember when Richard Pryor looked as cool as a pimp in church on Easter Sunday and appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and had this very humble, hilarious conversation about how he laced cocaine with rum and set himself on fire? Maybe I could have been funny like that. Not as funny as Richard Pryor. I mean, no one is as funny as Richard Pryor. But maybe if I had told my readers how funny my mother was, and also how uncaring and vain and, well, psychotic she was, maybe I would have made them like her more. Maybe the critics would have cared more about her and, in turn, cared more about me. And maybe I would have won a major award and sold more books. Imagine if I had been a little more accepting of my readers and softened their racial sentiments with a little joke or two. Imagine if I had poked fun at the stigma of schizoaffective disorder, adding a little sarcasm to it. I wish I’d been a bit more mischievous and changed my mother’s illness into a donkey’s head, making her appear mystical and completely insane, crowing at the moon.

Dorothy, I have to be honest with you, you kept me from laughing “hahaha.” No offense, but I’m surprised you’d give me this advice. When I was a young, passionate writer, I read your book, Bastard Out of Carolina. All I remember is crying so hard. I cried so hard I would have thought your character, Vaughn, was 100% autobiographical, not semi-autobiographical. I cried so hard I would have thought Vaughn and I were the same person and my story was her story. I cried so hard my therapist started to worry. To tell you the truth, I cried so hard I started to worry about whether the tears would come and when they would ever stop. Dorothy, I’m not the only one who feels that way. The New York Times wrote that your book features “birth and death, lots of accidents (horrible ones to think about), illness and sadness.” But it never said there was a lot of humor in it. But I think there was humor. So I believe your advice is true. You wouldn’t have done it if you didn’t really mean it, so here it is.

My mother once took a shit while doing the laundry. She had to fart, and in her own words, “just let it out!” After she took a shit, she called on me and all my siblings to share the anecdote, laughing at every word, sighing, “Oh my goodness,” and saying, “I wish one of you was here to witness it.” But the image it painted in our minds was certainly funnier than the act itself: my graceful, statuesque mother, in her pink satin feathered robe, with her trademark Virginia Slims dangling from the corner of her mouth, taking a shit while doing the laundry. Funny? I don’t know. Not that funny to me, but hey, family.

Let’s try again:

Shortly after she started using oxygen to treat her lung cancer and emphysema, my mother tried to smoke a joint and blew it in her face, blowing her dentures out of her mouth. She called for help from her sister, who was the closest, and of course she came, and my husband said, “I’ll come with you, because I’m not going to miss this.” No doubt memories of Tom and Jerry cartoons came to mind. A thick pink oval formed around my mother’s lips, surrounded by black faces in blackface, their white, wide eyes blinking to the lilting of piano keys. They both said she looked like Aunt Jemima before her transformation, or Elmer Fudd when Bugs put his finger in the barrel of a gun and it backfired, blowing Fudd’s face off. They also said they had a hard time containing their laughter when they looked under the bed and found my mother’s dentures still clenched in a joint.

Don’t get me wrong, Dorothy. I laughed for hours after I got off the phone with my sister. I laughed while telling the story to my husband. I laughed while telling it to my kids. I laughed so hard I was in tears. But, you see, no one in my family, not even my mother, is as funny as Richard Pryor.

Once, when I visited my mother in prison, she told me that she had started coughing up a little bit of blood every day. I was shocked and asked her, “Shouldn’t you see a doctor here? Are there no doctors here?” To be honest, I had no idea. For those of us who are free outside the bars, how can we make sense of a community surrounded by electric gates and barbed wire?

Dorothy, here’s something funny about visiting a felon’s mother in state prison. A felon’s mother is beyond reproach, so every question you ask is stupid. You’d think it would be the other way around, right? But it’s not. Because daughters aren’t supposed to visit their mothers in prison, every visit feels like I’m missing an apron. At home, I have nothing to turn to except my mother. But without my mother’s kitchen table and her cup of Red Ginger Celestial Tea and her cigarette smoke, I had no apron strings to connect me to my mother. Yes, she was my mother, but in prison she was #640702. It was a crime against the natural hierarchy, a pecking order turned upside down.

My mother knew, and she smiled at me with sympathy. She didn’t smile at me, Dorothy, but when I asked her, she just looked deadpan and said, “Yeah, we have doctors, but I’d rather die than be killed.” We burst out laughing, threw our heads back, laughed, wiped our tears, and my mother continued eating her Famous Amos chocolate chip cookies. She was serving an 8-25 year sentence for manslaughter and vomiting blood, and we were laughing and eating our cookies. But was that funny? I don’t know.

Dorothy, you know as well as I do that when you are poor – when you are poor on Similac powdered milk, instant ramen, powdered milk – humor is a means of self-medicating the pain. Whenever I tell my mother’s story, she is self-medicating. Maybe it’s a box of cookies, or Virginia Slims, or her favorite thick marijuana. And while I don’t know if I completely agree with you about using humor to lighten up a dark story, I do agree with the old adage that laughter is the best medicine. Laughter can’t cure cancer or prison time or poverty, but it can ease the symptoms. That’s why I didn’t use humor in the book. I didn’t want to ease the reader’s discomfort with being black or with mental illness. Maybe it was a mistake. Maybe I should have been more compassionate. Or would that be disingenuous? I don’t know. I really don’t know. But you’re the expert. So let me try again…